(Dickon Hall's biographical note)

This recent acquisition of paintings, drawings and studio and archive material adds to the existing collection held by Fermanagh County Museum to form a uniquely complete overview of T.P. Flanagan as an artist. Working and exhibiting over six decades, T.P. Flanagan was a leading figure in Irish art in the second half of the twentieth century. Seamus Heaney, a close friend for many years, described him as ‘one of the most accomplished landscape painters that Ireland has produced’[i], while The Times wrote that he was ‘beyond doubt the finest Irish watercolourist of his generation’[ii]. Colin Middleton spoke of his respect for Flanagan; he was ‘another man who is addicted to places’[iii].

Flanagan retained strong connections with Fermanagh throughout his life, and to Enniskillen in particular, the town where he had grown up and where he had received his first art lessons from Kathleen Bridle, who would remain a lifelong friend.

This collection of work by Flanagan and the

archive material now acquired alongside it also contribute towards a broader

understanding of Enniskillen’s own remarkable artistic history. Kathleen Bridle

was herself an excellent watercolourist who had studied in London at the Royal

College of Art and worked at the Harry Clarke glass studios in Dublin before

moving to Fermanagh. One of the sketchbooks included in this acquisition has a

number of studies towards Flanagan’s portrait of Bridle, which is in the

collection of Fermanagh County Museum. In 1927 she began to give lessons to

William Scott and the three subsequently became good friends. Scott, widely

regarded as one of the most significant post-war painters working in Britain,

is well-represented in the Fermanagh collection, as is Bridle, and in many ways

Flanagan can be seen as a link between the two, a passionate watercolourist who

also explored elements of abstraction within his work.

This collection of work by Flanagan and the

archive material now acquired alongside it also contribute towards a broader

understanding of Enniskillen’s own remarkable artistic history. Kathleen Bridle

was herself an excellent watercolourist who had studied in London at the Royal

College of Art and worked at the Harry Clarke glass studios in Dublin before

moving to Fermanagh. One of the sketchbooks included in this acquisition has a

number of studies towards Flanagan’s portrait of Bridle, which is in the

collection of Fermanagh County Museum. In 1927 she began to give lessons to

William Scott and the three subsequently became good friends. Scott, widely

regarded as one of the most significant post-war painters working in Britain,

is well-represented in the Fermanagh collection, as is Bridle, and in many ways

Flanagan can be seen as a link between the two, a passionate watercolourist who

also explored elements of abstraction within his work.Flanagan left Belfast College of Art in 1955, part of a

group of painters that also included Basil Blackshaw, Cherith Boyd and Martin

McKeown, who quickly established themselves in the Belfast art world; a lively

early painting dating from these years at college shows Flanagan and Blackshaw

at work on canvases alongside their contemporary Kenneth Jamison, who went on

to become the director of the Arts Council of Northern Ireland and a prolific

writer on art. Flanagan’s work had already been acquired by the legendary

Belfast collector Zoltan Frankl.

a lively

early painting dating from these years at college shows Flanagan and Blackshaw

at work on canvases alongside their contemporary Kenneth Jamison, who went on

to become the director of the Arts Council of Northern Ireland and a prolific

writer on art. Flanagan’s work had already been acquired by the legendary

Belfast collector Zoltan Frankl.

He had also become friendly in the early 1950s

with a renowned Ulster painter of an earlier generation, Colin Middleton, and

they occasionally ventured on painting trips together. The loose handling and

sense of drama implicit in a landscape in Flanagan’s early work is at times

close to Middleton in paintings of this period such as Ardglass Harbour.

He had also become friendly in the early 1950s

with a renowned Ulster painter of an earlier generation, Colin Middleton, and

they occasionally ventured on painting trips together. The loose handling and

sense of drama implicit in a landscape in Flanagan’s early work is at times

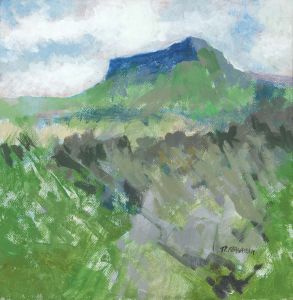

close to Middleton in paintings of this period such as Ardglass Harbour. Autobiography is a constant element within Flanagan’s work

and this understanding of the power of storytelling is perhaps connected with

his early literary ambitions, which became subsumed into his approach to

painting. As a child, Flanagan spent months each summer with his two aunts, who

lived on the estate at Lissadell, near Sligo, and the house and demesne had a

powerful and enduring effect on him, both visually and imaginatively. His

enduring love of the landscape around Sligo is evident in a later painting such

as Ben Bulben.

Autobiography is a constant element within Flanagan’s work

and this understanding of the power of storytelling is perhaps connected with

his early literary ambitions, which became subsumed into his approach to

painting. As a child, Flanagan spent months each summer with his two aunts, who

lived on the estate at Lissadell, near Sligo, and the house and demesne had a

powerful and enduring effect on him, both visually and imaginatively. His

enduring love of the landscape around Sligo is evident in a later painting such

as Ben Bulben.

There is a strongly literary quality to these works that was to remain within Flanagan’s painting, a dimension of imagination alongside the visual image, and this interest in image as metaphor remained significant within Flanagan’s work, a metaphor for both personal experience and also broader, more universal ideas. Flanagan imbues these houses with his own recollections, with the imagined

experiences of those who lived and worked there and with their own intrinsic

history and environment.

There is a strongly literary quality to these works that was to remain within Flanagan’s painting, a dimension of imagination alongside the visual image, and this interest in image as metaphor remained significant within Flanagan’s work, a metaphor for both personal experience and also broader, more universal ideas. Flanagan imbues these houses with his own recollections, with the imagined

experiences of those who lived and worked there and with their own intrinsic

history and environment.

Flanagan first began to paint Castle Coole in 1974 as part

of an extended commission, but the house and its demesne would become a major

part of his later work.  While the elegant neo-classical proportions of the

house imbue these images with a clear sense of structure and form, the

technique of watercolour that Flanagan often preferred adds a richer and more

complex mood, a suggestion of the shifting effects of time, something that

celebrates the enduring presence and identity of the house beyond a

straightforward visual description.

While the elegant neo-classical proportions of the

house imbue these images with a clear sense of structure and form, the

technique of watercolour that Flanagan often preferred adds a richer and more

complex mood, a suggestion of the shifting effects of time, something that

celebrates the enduring presence and identity of the house beyond a

straightforward visual description.

The painting of the saloon at Castle Coole already in the collection of Fermanagh County Museum, for which a detailed preparatory drawing

is in this recent acquisition, is in many ways balanced by the two watercolours

included in this group. They also have an elegantly architectural structure,

but by including exterior, as well as interior subject matter, they broaden out

our imaginative experience of the house, recalling the manner in which

Flanagan’s experience of Lissadell was based on the diverse lives of those

working on the estate.

The painting of the saloon at Castle Coole already in the collection of Fermanagh County Museum, for which a detailed preparatory drawing

is in this recent acquisition, is in many ways balanced by the two watercolours

included in this group. They also have an elegantly architectural structure,

but by including exterior, as well as interior subject matter, they broaden out

our imaginative experience of the house, recalling the manner in which

Flanagan’s experience of Lissadell was based on the diverse lives of those

working on the estate.

Flanagan’s engagement with specific landscapes in Ulster, in which he developed an imaginative and expressive modernist aesthetic to explore, alongside their visual qualities, the physical and mystical aspect of places that he knew intimately, provided a substantial contribution to the creation of a post-war landscape tradition in Northern Irish art and one that stands alongside those of his contemporaries such as Colin Middleton and Basil Blackshaw. This particular examination of place in the context of local history, memory and myth also placed Flanagan close to poets such as Seamus Heaney and Michael Longley. The unusually literary qualities in Flanagan’s work gave him a unique role at the centre of this construction of a rich and complex Ulster identity.

This repeated examination of a landscape requires intense

concentration, so that the places that Flanagan has been drawn to paint have

been those where he has been able to spend significant amounts of time, such as

Lough Erne and north Donegal. He has almost become synonymous with certain

places through this immersion. The Gortahork Series, first inspired by a visit

to Donegal in 1966 when the Flanagan and Heaney families travelled there

together, is very different in mood from Flanagan’s paintings of Lissadell and

Castle Coole, evoking a dominantly physical response to the landscape, as in A Stream through Sand.

This repeated examination of a landscape requires intense

concentration, so that the places that Flanagan has been drawn to paint have

been those where he has been able to spend significant amounts of time, such as

Lough Erne and north Donegal. He has almost become synonymous with certain

places through this immersion. The Gortahork Series, first inspired by a visit

to Donegal in 1966 when the Flanagan and Heaney families travelled there

together, is very different in mood from Flanagan’s paintings of Lissadell and

Castle Coole, evoking a dominantly physical response to the landscape, as in A Stream through Sand.

S.B. Kennedy commented that the ‘Gortahork pictures mark a watershed in Flanagan’s career; henceforth he enters his maturity, his subject matter and aesthetic, his technique and voice are all resolved and are completely his own[iv]. This charged approach to landscape has a parallel in Seamus Heaney’s writing, and the two were particularly close at this time and worked together on a number of projects.

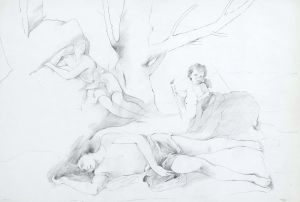

Among these recent acquisitions is one of the

most notable works dealing with the early years of the Troubles that was made

at that time. The Victim was painted

in response to the murder of Flanagan’s friend Martin McBirney in 1974; it is

both a ‘personal requiem’ but also is given a greater resonance and complexity

through Flanagan’s decision to create a figure inspired by Poussin and to avoid

any notable detail beyond the pale, shrouded figure. Despite the physical

impact of its near life-size scale, the painting has a strong sense of silence

and impersonality, and an elegance that almost seems to defy the facts of its inspiration, with only

the foot beyond the shroud a stark reminder of the human loss expressed here.

Among these recent acquisitions is one of the

most notable works dealing with the early years of the Troubles that was made

at that time. The Victim was painted

in response to the murder of Flanagan’s friend Martin McBirney in 1974; it is

both a ‘personal requiem’ but also is given a greater resonance and complexity

through Flanagan’s decision to create a figure inspired by Poussin and to avoid

any notable detail beyond the pale, shrouded figure. Despite the physical

impact of its near life-size scale, the painting has a strong sense of silence

and impersonality, and an elegance that almost seems to defy the facts of its inspiration, with only

the foot beyond the shroud a stark reminder of the human loss expressed here.

This subtlety, the search for a suitably evocative image that avoids a literal analysis of the facts of the Troubles while acknowledging the tragedy of events, is at the heart of Flanagan’s response.

As such, The Victim is a remarkable counterpart to A Ulster Elegy, 1971, in the collection of Fermanagh County Museum. Ostensibly a landscape, An Ulster Elegy uses a highly abstracted series of forms and marks to refer to visual aspects of the place and the history of Lough Erne, in particular the story of the loss of two brothers in its waters in the dark, unaware that they were only yards from the shore as the lake froze around them.

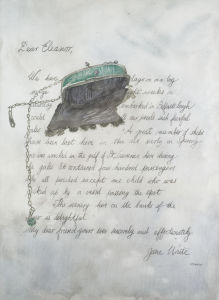

The same powerful use of metaphor is evident in the Emigrant Letters series of which one, Dear Eleanor, is included in this acquisition. They demonstrate Flanagan’s interest in language and powerfully express the ideas of memory and stillness that are so central to his work. They encourage an emotional engagement with themes that also connect with his other more political paintings.

Over a number of years Flanagan engaged with the problematic nature of evolving an appropriate visual response to events that were evolving so quickly and with such enormous impact, establishing a consistency and seriousness of approach. At times oblique and complex, these works sought more universal resonance across a divided society.

An Ulster Pastoral,

painted in 1991, is a later return to this theme but addresses it more directly,

imposing the awkwardly stacked geometry of a watchtower on the untouched

landscape which would be more familiar in Flanagan’s work. Again he avoids

specific comment to make a broad statement on the impact of the Troubles,

seeing sadness and tragedy in the altered landscape, a shared space and

identity that he suggests might be a unifying point for all sides.

An Ulster Pastoral,

painted in 1991, is a later return to this theme but addresses it more directly,

imposing the awkwardly stacked geometry of a watchtower on the untouched

landscape which would be more familiar in Flanagan’s work. Again he avoids

specific comment to make a broad statement on the impact of the Troubles,

seeing sadness and tragedy in the altered landscape, a shared space and

identity that he suggests might be a unifying point for all sides.

Flanagan’s later landscapes, such as In Moonlight, Ben Bulben

or Carrickreagh Quarry seem to find

more peace with the landscape and a direct interest in the visual aspects of

new and familiar motifs. The latter has a strong structure and recalls Cezanne’s

paintings of the quarry at Bibémus, with a concentration on formal

structure that is barely softened by occasional trees.

Flanagan’s later landscapes, such as In Moonlight, Ben Bulben

or Carrickreagh Quarry seem to find

more peace with the landscape and a direct interest in the visual aspects of

new and familiar motifs. The latter has a strong structure and recalls Cezanne’s

paintings of the quarry at Bibémus, with a concentration on formal

structure that is barely softened by occasional trees.

This acquisition joins together with the works already in the Fermanagh collection to form a major assessment of T.P. Flanagan as a painter. Alongside a strong biographical dimension, it sets out the major themes of his career through a series of significant and more intimate works. It demonstrates Flanagan’s approach to working across a diverse range of scales and media. Not only does it set out his contribution to the post-war Ulster landscape tradition, it also includes some of the most significant paintings made in response to the early years of the Troubles, exploring the complexity of formulating a response to these events.

Fermanagh remains a constant theme; it is a subject to which he returned, as in the series of paintings of Lough Erne and Castle Coole, and it is also deeply embedded in Flanagan’s artistic identity. He himself credited his love of watercolour, in which he worked prodigiously and with great skill, to the teaching of Kathleen Bridle, who was herself an exemplary watercolourist. These paintings provide a fascinating counterpoint to Bridle’s paintings within the Fermanagh collection and also, intriguingly, to those of William Scott. Scott often related his table top still life paintings, such as Still Life with Garlic, to memories of austere kitchen implements on the kitchen table in his childhood, and it is interesting to consider whether some memory of the light of Fermanagh seeped into Scott’s 1963 White and Grey, as it seems to have in Flanagan’s Ulster Elegy, for example.

The archive material within this acquisition will no doubt become central to much further research into Flanagan’s work, revealing much of his working methods in sketchbooks and collages, but it is also a reminder of his place, alongside his wife Sheelagh, at the nexus of a crucial series of connections in twentieth century art and cultural life in Northern Ireland. Their lengthy friendships with William and Mary Scott, Seamus and Marie Heaney, F.E. and Beth McWilliam, John and Roberta Hewitt and others are documented in letters. It seems entirely appropriate that the town in which T.P. Flanagan’s aspirations as a writer and artist were first shaped should be home to such a notable record of his life and achievement.

[i] Heaney, Seamus, ‘Foreword’, T.P. Flanagan: Painter of Life and Landscape, Lund Humphries, Surrey, 2013 p.11

[ii] The Times, 16th April 2011

[iii] Michael Longley, ‘Talking to Colin Middleton’, Irish Times, 7th April 1967

[iv] S.B. Kennedy, T.P. Flanagan: Painter of Life and Landscape, p.63

[v] Christina Kennedy, ‘Classical Watermarks’, Irish Arts Review, Volume 9, 1993, p.144