In a work such as ‘Ulster Pastoral’ with its ironic title (1991) the artist registers the imposition of an army watchtower on the landscape. However two of Flanagan’s most layered works related to the Northern Ireland political troubles are ‘Ulster Elegy’ (1971) and ‘Victim’ (1974). It has to be said Flanagan dislikes art that verges on the propagandistic but acknowledges the power of TV reportage of political or violent events with which he does not want to compete. He has never felt the need to be a commentator for the moment – ‘everything has to be retrospective’. [Conversation with the Author]

In a work such as ‘Ulster Pastoral’ with its ironic title (1991) the artist registers the imposition of an army watchtower on the landscape. However two of Flanagan’s most layered works related to the Northern Ireland political troubles are ‘Ulster Elegy’ (1971) and ‘Victim’ (1974). It has to be said Flanagan dislikes art that verges on the propagandistic but acknowledges the power of TV reportage of political or violent events with which he does not want to compete. He has never felt the need to be a commentator for the moment – ‘everything has to be retrospective’. [Conversation with the Author]

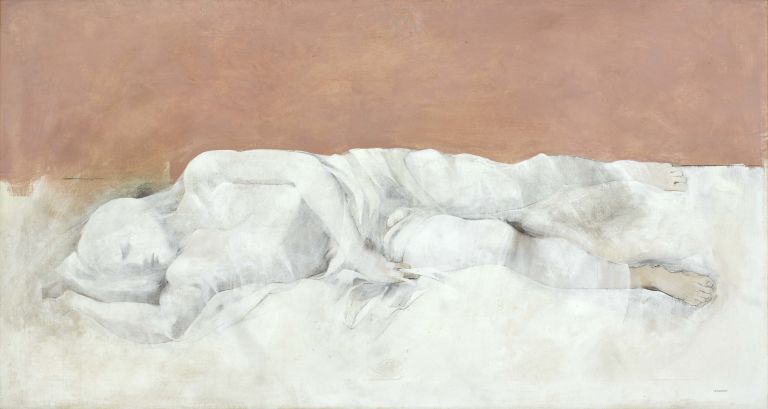

Such was the case with ‘Victim’, which relates to the murder of Belfast Judge Martin McBurney, a friend of the artist. McBurney was shot dead while cooking breakfast and still in his dressing gown. As reported on TV his body was removed on a stretcher covered by a light sheet and, as witnessed by the artist, with a foot protruding, making the scene more poignant.

Flanagan’s response in painting ‘Victim’ was to avoid, with a suitable time lag, the actual in reportage and adopt a timeless archetypal neo-classical figure. His treatment of the figure is conditioned by two factors – his admiration for Nicholas Poussin and his travels in Italy and Greece.

‘Victim’ (1974) draws on Poussin’s ‘Echo and Narcissus’ as a pictorial and moral source. Poussin’s works carry a gravitas, solemnity and poetic mood in his handling of mythological themes. As such it provided the timeless quality Flanagan required. ‘Victim’ is about all victims everywhere regardless of time and place. The other enabling source was the Tuscan tombs he had visited while in Italy. The earth red used as a neutral and still backdrop in the painting also contributes to the universal outreach rather than merely the local reference. The work for me also recalls the dignity of the Dying Gaul (Roman copy after the Greek original)

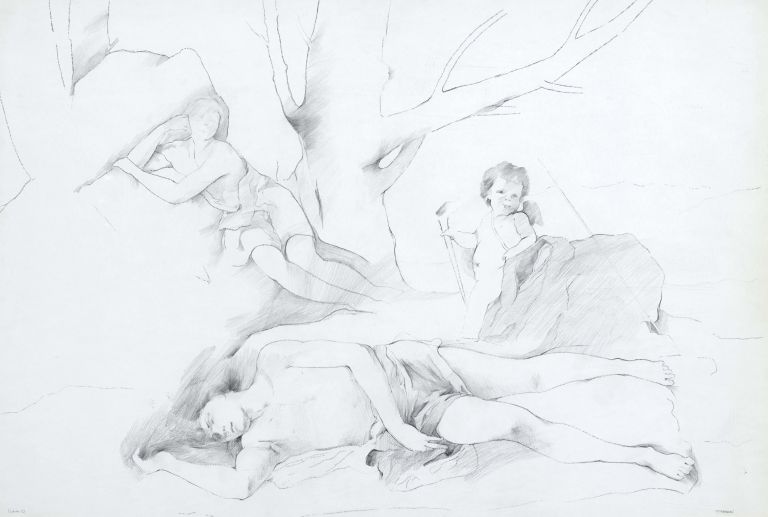

Drawing has always been important to Flanagan and his experience as a student under Romeo Toogood at The Belfast College of Art were work in the life room was important. A book ‘The Art and Craft of Drawing’ by Vernon Blake advocated by Toogood and impressed the young student and its impact remained with him. One of its recommendations is that if you want to learn how to paint a landscape, learn how to paint the nude. Flanagan made several studies of Poussin’s ‘Echo and Narcissus ‘out of which his draped classical solution for ‘Victim’ emerged.

‘ Poussin’s paintings have been a source of pleasure and inspiration throughout my career for their superb ability to combine and relate all the elements of picture making with a profound human understanding. At this stage of my life I very much agree with Cezanne, who claimed ‘everytime I come away from a Poussin I have a better idea of myself ‘. [Conversation with the Author]

‘Victim’ is frozen in time and in ‘Ulster Elegy’ (1971) this condition is extended, inter alia, to the frozen politics and attitudes of Northern Ireland. Flanagan has long painted Lough Erne – its changes of mood, plotting in its islands as horizontal stretches or building verticals from bulrushes but always passing the experience of landscape through a personal filter.

‘Ulster Elegy’ relates on one level to the tragic story of a postman William Rooney being frozen to death in his boat on Upper Lough Erne during extreme weather conditions in December 1961. His brother James was also drowned trying to rescue him. When William’s body was finally found beneath the ice his ‘….body was enthroned as in a glass coffin’ [Seamus Heaney, ‘T.P.Flanagan’ in Rosc ’71 The Irish Imagination, ed. Brian O’Doherty,1971], recalling John Everett Millais’ Ophelia (1851/52).

Flanagan in painting this elegiac response avoids any narrative content or detail and allows his structuring and re-structuring of the elements in the landscape to carry the tragic and emotional charge. On the right hand side of this diptych a black boat is blocked in under a foreboding sky and what may be read as white petals discretely form a floral tribute. The left hand side is semi-abstract with an amalgam of swirling stokes and circular forms conjuring up a deconstructed Celtic cross. The diptych form allows for purposeful juxtapositions and correspondences within and between its two elements. Here stillness is off set by flux and by extension the turbulence of the times in Northern Ireland where frozen attitudes underpin progress and prevent events to be assimilated into history. ‘Ulster Elegy’ is about being trapped in perpetuity.

Extract from 'T.P. Flanagan - Correspondences' by Professor Liam Kelly. See here for the full essay. The text has been reproduced through the T.P. Flanagan Collection project supported by The National Lottery Heritage Fund, the Art Fund and the Friends of Fermanagh County Museum